Later works add episodes to the beginning that culminate in the "Mystical Marriage" discussed below.

Symeon's passion and its western derivatives follow this order of narrative:

- In Alexandria Catherine, an erudite virgin of royal lineage, objects to the Emperor Maxentius' calling for a grand festival in honor of the gods. One portrait in the Getty alludes to Catherine's erudition by showing her reading a book and another uses a book as an attribute. Her royal lineage leads the artists almost invariably to give her a crown, as in the first picture at right.

- Maxentius summons fifty pagan philosophers to debate Catherine (image). But she prays for God's assistance, and the philosophers lose the debate, convert to Christianity, and are martyred in what Catherine assures them is a Baptism by Fire. At Notre-Dame de Morillon in France the earliest known image of St. Catherine's story shows the martyrdom of the philosophers inside a structure shaped like a baptismal font.

- Maxentius promises that Catherine can be his co-ruler if she recants, but she refuses, saying she is a bride of Christ. So Maxentius has her whipped (image). She is then imprisoned for twelve days (forty in Capgrave). In the western versions angels tend her wounds with salve (image). Wishing to be a Christian like Catherine, the Emperor's wife visits her in prison, accompanied by the military officer Porphyry (image). During the confinement, Catherine is fed daily by a dove from Heaven (image); Christ also visits in person to encourage her.

- After the twelve days Maxentius offers Catherine her life if she recants, death if she persists in error. She refuses, so he has an engine with spiked wheels built to frighten her into submission. She prays and an angel destroys the engine. The flying fragments kill many pagan bystanders (image). The Golden Legend has a very confusing account of the engine's construction and may be the cause of some very odd visualizations in the art (example).

- Maxentius' wife objects to his behavior, so he has her tortured and put to death. Then Porphyry and his 200 men confess the faith and are also martyred.

- Again refusing Maxentius' offer, Catherine is condemned to death. Women follow weeping behind her to the place of execution, but she says they should rejoice for her and weep for themselves.2

- She prays for those who will remember her when they pray, and then she is beheaded (image). Three miracles are noted: Milk flows from her trunk when she is beheaded, angels carry her body to Mt. Sinai (image), and a healing oil flows from her sarcophagus.

The giving of the ring became a popular subject in the art, but the question facing artists was how to handle the implications of sexual intimacy in such a subject. One early example from the 14th century deals with the problem by putting Jesus and Catherine at arms' length on the left and right of the scene. Subsequent images picture Christ as a baby on his mother's lap (example). The original for this device may be a fresco in Montmorillon from about 1200 in which the Christ Child reaches out from his mother's lap to place a crown on St. Catherine's head.

In Capgrave's Life "ten or twelve virgins…beautiful and splendidly clothed" stand about the saint.5 But in the art the wedding is attended either by angels (example) or by other popular saints, especially St. John the Baptist and St. Anthony Abbot (example). Tintoretto's fresco in Venice's Ducal Palace even puts the Doge in the picture. (The Tintoretto is a rare case where the baby puts the ring on a finger of Catherine's left hand rather than her right.)

PORTRAITS

In portraits St. Catherine's most common attribute is a spiked wheel from the ruined engine. Also common are the sword used in the beheading, and sometimes a book (example). In this painting from the 16th century the attribute is the ring she received from Jesus. An alabaster relief from Spain opts instead to show her enthroned and treading the head of Maxentius. Throughout the high Middle Ages and Renaissance she is among the saints most likely to be included in group portraits with the Virgin and Child (example) and with other virgin martyrs such as Margaret (example), Barbara (example), or Agnes (example). The palm of martyrdom, as in the second picture on the right, is of course common in these portraits.The great popularity of St. Catherine portraits may be due to her final prayer before the execution. In Symeon, she merely asks that Christ will grant people "petitions that are profitable to them" when they call on his name through her. But in the Passio she prays that he will grant the requests of those in need who invoke her against pestilence, famine, illness, and calamities – and for healthy air and a fruitful harvest. Later versions of the prayer keep repeating this list through the rest of the Middle Ages, and by the 14th century Catherine has become a Nothelfer, one of the fourteen "Holy Helpers" to whom people looked for assistance when in need.

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University.

HOME PAGE

St. Catherine with all her attributes and Maxentius at her feet. (See the description page for details and commentary.)

Detail from Vivarini, Polyptych of the Virgin and Child, 1449 (See the description page)

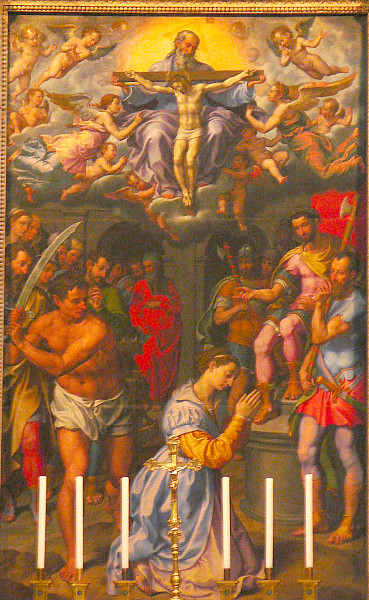

Maxentius presides at the execution of St. Catherine, presented in this image as a participation in the sacrifice of Christ in the upper register, where it is the Father who presides. (See the description page.)

ATTRIBUTES

- Spiked wheel, broken

- Sword

- Crown

MORE IMAGES

- 1344: Detail from Guariento di Arpo's Coronation of the Virgin altarpiece.

- 1370: In the Nativity window at Regensburg Cathedral, a panel with SS. Catherine and Agnes.

- 1390s: A portrait of St. Catherine with the wheel peeking out from beneath her mantle is included in the right wing of Cenni di Francesco's Coronation of the Virgin Altarpiece.

- 1442: Bernat Martorell's Saints Michael, Eulalia, and Catherine of Alexandria.

- 1475-80: The saint is pictured in the lower register of a composite stained glass window from England.

- 16th century: Embroidered roundel of St. Catherine on a chasuble.

- 1505: Catherine is one of three saints in a high relief in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome.

- 1518: The Beheading of St. Catherine, a stained glass window in Munich.

- 1540: In Tintoretto's Madonna and Child with Saints the traditional wheel is just one part of a scary-looking contraption.

- 1565-70: Veronese's Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria underlines the connection between the "wedding" and Catherine's eventual martyrdom.

- Last third of 16th century: The Resurrection of the Body of St. Catherine.

- Beginning of the 18th century: Jacopo Amigoni's St. Catherine and St. Andrew in San Stae, Venice.

- First decade of the 17th century: St. Catherine is half-disrobed in Gaudenzio Ferrari's unusual portrait of her at the torture wheel.

- 1750: In the margin of a Mexican nun's badge of the Annunciation.

- 1753: In the margin of a Mexican nun's badge.

- 19th century (?): Pew backs with the Madonna, Blaise, and Catherine of Alexandria.

- Undated: Painting in a 9th-century convent with attributes characteristic of high- or late-medieval images.

- St. Catherine's statue is among the eight that flank Peter and the Virgin Mary in the St. Peter Altarpiece at the "Frari" in Venice.

NAMES

- "Catherine" is sometimes spelled with a "K," especially in Middle English lives.

DATES

- Feast day: November 25

BIOGRAPHY

- Golden Legend #172: html or pdf.

- The 14th-century Czech Life of St. Catherine of Alexandria translated in Head, 763-79.

- Winstead's translation of Capgrave's 15th-century Life.

- Catherine's vita in The Roman Breviary: English translation, IV, 768-53; Latin original, 1112-1113

- Butler, 420-21.

- The 12th-century Middle English Legend of St. Katherine of Alexandria.

- Bokenham, 159-185.

- Early South English Legendary 92-101.

- Symeon Metaphrastes, Martyrium Sanctae et Magnae Martyris Aecaterinae, in Migne, Patrologiae Grecae Cursus Completus, CXVI 275-302.

- The 11th-century Passio Sanctae Katharinae Alexandriensis.

- Albert Poncelet, "Sanctae Catharinae Virginis et Martyris Translatio et Miracula," Analecta Bollandiana, XXII (1903), 423-38.

- Paul Peeters, "Une Version Arabe de la Passion de Sainte Catherine d'Alexandrie" [with translation into Latin], Analecta Bollandiana, XXVI (1907), 5-32.

NOTES

1 Symeon Metaphrastes, Vita Sanctorum in Migne, Patrologiae Grecae Cursus Completus CXVI 275-302, and see the Biography listings above. For an overview and critique of the forms of the legend focused on the debate with the philosphers, see Robertson, 53-68.

2 The Golden Legend omits the weeping women; the 11th-century Passio places them in the wheel episode.

3 Symeon, cxvi, 291. Passio, 19. In the latter when Catherine dies Christ also echoes the bridegroom's words in the Song of Solomon (2:10, 4:8, 5:1): "Come, my beloved, lo the gates of blessedness have opened for you."

4 Head, 770-775.

5 Capgrave, 92.