The veil may be due to her early portraiture in the East. In a 6th-century mosaic in the Euphrasian Basilica in Poreč, she is presented as a noblewoman in a veil. Her portrait in Monreale Cathedral gives her a veil and follows the Eastern tradition of having her hold a hand cross.

NARRATIVE IMAGES

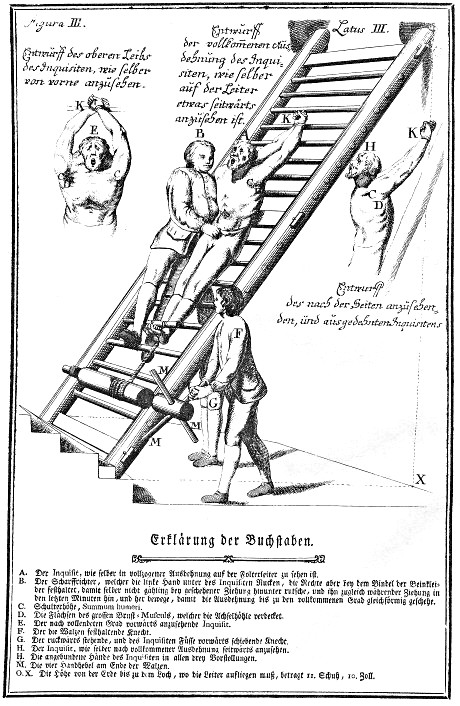

In the first part of Agatha's story, she spurns the pagan provost Quintianus' offer of marriage, so he consigns her to a brothel to soften her resolve. But the madam finds her intractable, so the provost calls her back to him, argues and threatens, and finally has her put in prison.The next day he has her stretched on an equuleus (fourth picture at right), a device of whose nature many medieval writers and artists seem to have been blissfully unaware. Caxton renders the word as "a tree" (that is, a beam or pole), and most narrative images either make it a low gibbet (example) or, like the second picture at right, omit picturing the device at all.1

Both those images actually show Agatha at the next stage of her passion, the cutting off of her breasts, which is the most common element in the narrative images. The implement used is normally a pair of pincers, or sometimes two pair, as in the second picture at right.

When the saint still refuses to deny her faith, Quintianus orders that she be imprisoned without food, drink, or medicine for her wounds. At this point she is visited by St. Peter in the guise of an old man. In the Passio, Peter simply brings Agatha new breasts. But the Golden Legend's account from two or three centuries later is more complicated. Not recognizing Peter, Agatha refuses human healing because "I have my Lord Jesus Christ, and he by a single word can cure everything.…If he so wills, he can cure me instantly." Peter reveals himself, tells her she is healed in Jesus' name, and vanishes. It is not until then that she prays and finds that her breasts have been restored.

Despite the widespread influence of the Golden Legend, I have found only two images that follow faithfully this complex account of Agatha's cure, one by depicting the saint's refusal and one dramatizing Peter's reply. The few other images I have found, two by Alessandro Turchi and one by Giovanni Lanfranco (third picture at right), go with the earlier version in which Peter heals the saint directly.

THE PROBLEM OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE

In "Saint Agatha and the Sanctification of Sexual Violence" Martha Easton concedes that the "relationship between Agatha's torture and the Crucifixion allows the viewer to use the image as a means of religious contemplation" (Easton, 97), but she also explores a number of perhaps less healthy kinds of viewer response from feminist and Freudian viewpoints. Jill Burke's essay on Sebastiano's Passion of St. Agatha (second picture at right) argues that it was pornographic by design, heralding "a new genre of images, one that deliberately, and intentionally, exploited equivocal – and sometimes contradictory – social notions about flesh, sexuality, and spirituality" (Burke, 492).When these images are on display in churches, it may be a challenge to guide the viewer from the sight of severed breasts to a state of religious contemplation. The Church of Saint Agatha in Sant'Agata da Feltra does this by means of a large canvas that skips ahead to Agatha's arrival in Heaven, where she offers her breasts on a plate to the Virgin and Child, fully dressed and with the ample figure restored to her that night in prison. On the other hand, in Trastevere's Church of St. Agatha a huge painting behind the altar of the torturer going at the breasts of the half-naked saint forces viewers who enter the church to work out for themselves those contradictory "notions about flesh."

SAINT AGATHA AND SAINT LUCY

The Golden Legend's story of St. Lucy begins with a visit to the sepulchre of St. Agatha, who intercedes with Christ to heal Lucy's mother of a bloody flux. The Metropolitan Museum in New York has a painting of this episode by Giovanni di Bartolommeo Cristiani.FOR FURTHER READING

Easton and Cheney provide very thorough introductions to St. Agatha iconography, with a wealth of images and references to original sources and modern criticism.

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University.

Detail from a Syracuse Virgin Enthroned, mid-15th cent. (See the description page.)

Sebastiano del Piombo, The Passion of St. Agatha, 1520 (See description page)

Giovanni Lanfranco, St. Peter Healing St. Agatha, 1614 (See description page)

An equuleus ("rack") is a ladder-like device used in ancient Greece and Rome. Ropes and rollers at one or both ends pull the victims' limbs from their bodies. (Source: this page at Wikimedia Commons.)

ATTRIBUTES

- Primary attribute: breasts on a platter

- Attribute used from time to time: pincers

- Attribute of martyrdom: palm branch

MORE IMAGES

- 1410-1420: Like several other medieval images, this fresco in a German church misunderstands the Latin equuleus and assumes it means a sort of low gibbet.

- 2nd half of the 16th century: In the predella of a retable in Salamanca.

- 1580: In Bassano's Madonna and Child in Glory and Saints Agatha and Apollonia a sort of treasure chest sits half-hidden behind Agatha's back, symbolizing her refusal of the "great promises of temporal goods" that the madam offered her if she would give in to Quintinianus.

DATES

- Feast day: February 5

- Died in 251

BIOGRAPHY

- Golden Legend: html or pdf

- Bokenham, 157-66

- Early South English Legendary, 193-97

- Acta Sanctorum, February vol. 1, 595-656

- Agatha's vita in the Roman Breviary for February 5 — English translation: I, 747-48. Latin original: 822-24.

- Life of St. Agatha in Migne's text of Metaphrastes, CXIV, 1329-40.

ALSO SEE

NOTES

1 Also note a Passio Sanctae Agathae (Bibliothèque Nationale MS. lat. 5594, fol. 69), where the saint hangs by the neck from a low gibbet to illustrate the phrase iussit eam in eculeo ingenti suspendi ("he ordered her suspended on a huge rack"). The manuscript page is online at the BN's website (retrieved 2022-06-21). The manuscript's Agatha miniatures are analyzed in Winstead, 29-33. William Caxton is similarly at a loss over the word eculeus. In his account of St. Vincent's passion he renders the word as "the place named eculeus." In St. Quentin's story it is "an instrument to torment saints on," and in that of Saturninus of Rome it is "the torment named Eculee."