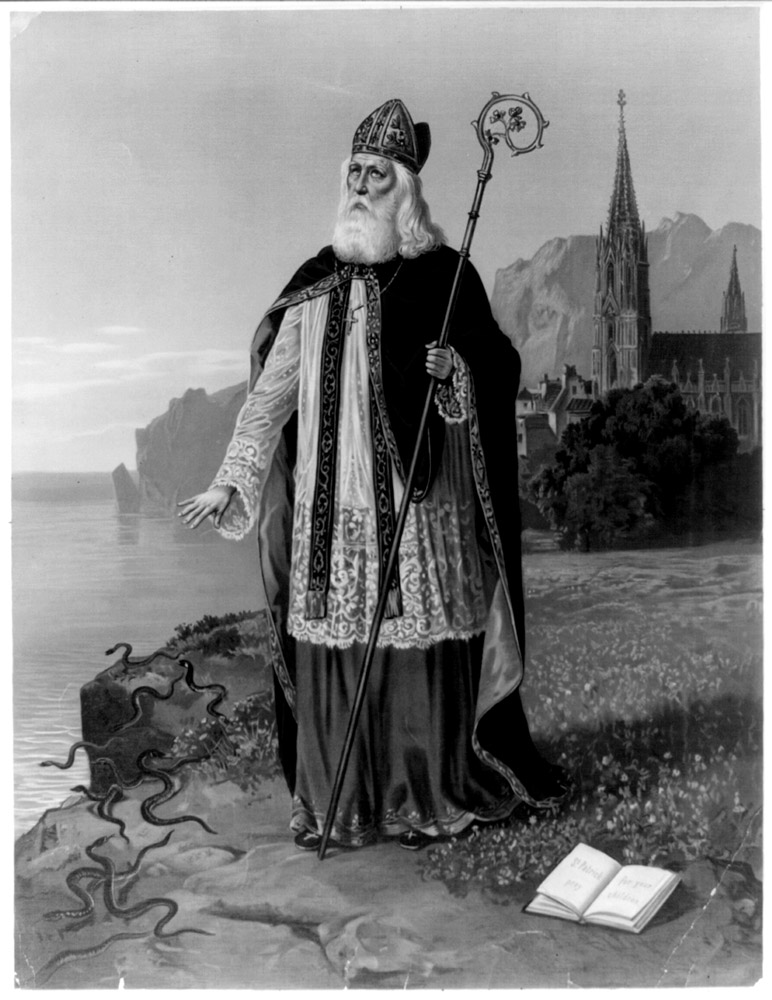

After the Middle Ages he was most often portrayed as at right: a bearded bishop with a mitre, crozier, and chasuble. The chasuble is most often green but sometimes red. Many images dispense with attributes and rely on a label or the green color of the chasuble. The two attributes that do feature in other images are a shamrock and one or more snakes at his feet.

THE SNAKES AND THE SHAMROCK

Snakes allude to the belief, retold in the Golden Legend, that he drove the snakes out of Ireland. The shamrock, according to Rachel Moss, was strongly associated with St. Patrick by the late 17th century. People wore shamrocks on March 17, and halfpennies minted in Dublin showed him holding one in his right hand. However, "there was no historical basis for the association of the Saint with the plant" (Moss).Today's Catholics are told that St. Patrick used the shamrock to explain the Trinity. I have not been able to find any pre-modern text that makes this claim, but it is true that some of the earliest biographies report an emphasis on Nicene theology. One text has him tell the daughters of an Irish king that God the Father "hath a Son coeternal with himself and like unto Him. But the Son is not younger than the Father, nor is the Father older than the Son" (Stokes, 103). And he opens "The Deer's Cry" with the words "I bind myself today to a strong virtue, an invocation of the Trinity. I believe in a Threeness with confession of an Oneness in the Creator of the universe" (ibid., 49).

NARRATIVE IMAGES

Usually narrative images focus on St. Patrick's work of conversion in Ireland, as in (this stained glass) and in the 15th-century fresco cycle in the Church of San Patrizio in Colzate, Italy.1 One may also find images of "St. Patrick's Purgatory" (example). In the Golden Legend, Patrick opened a pit in the earth "in to which whomsoever entered therein he should never have other penance ne [nor] feel none other pain, and there was showed to him that many should enter which should never return ne come again. And they that should return should abide but from one morn to another, and no more, and many entered that came not again." The Latin (but not Caxton's translation) then tells of a man who withstood the pains and survived the experience because he kept saying, "Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, have mercy on me, a sinner" (Ryan, I, 194. Also see Acta Sanctorum, March vol. 2, 585-89).

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University

HOME PAGE

St. Patrick as a bishop with a green chasuble (See description page)

With the shamrock (See description page)

With the snakes (See description page)

DATES

- Feast day: March 17

- 5th century

BIOGRAPHY

- Golden Legend #50

- Whitley Stokes, The Tripartite Life of Patrick: With Other Documents

- Jocelin of Furness's Life (in Latin) is in Acta Sanctorum, March vol. 2, 536-77.

- Vita Patricii, ex Libro Armachano.

- Muirchu Maccumachtheni, Vita Sancti Patricii, in Analecta Bollandiana, I, 531-85

ALSO SEE

- Rachel Moss, "The Staff, the Snake and the Shamrock"

NOTES

1 Many of the Colazate frescos have been at this page on Wikimedia Commons (retrieved 2021-12-05). The panel illustrating his baptism of Irish converts is published in One Hundred Saints, 139).