Saints Justina & Prodoscimus of Padua and Saints Justina & Cyprian of Antioch

THIS PAGE HAS BEEN REPLACED BY justinaPadua.html AND justinaAntioch.html. I AM LEAVING IT ONLINE BECAUSE SOME READERS MAY HAVE BOOKMARKED IT, BUT PLEASE SEE THE NEW PAGES.

Artists sometimes confuse the two Justinas, so we will look at each one separately and then discuss how their respective images may be identified.

JUSTINA AND CYPRIAN OF ANTIOCH

The story of Justina and Cyprian of Antioch is told in the Golden Legend. Originally Cyprian was a wicked magician who enlisted the devil in his designs on the virtue of Justina, who had become a Christian after hearing a priest read the gospel. The devil kept trying, but every attempt failed when Justina would make the sign of the Cross. The devil had to admit to Cyprian that "the crucified God" was stronger than he, so Cyprian renounced his relationship with the devil and became a Christian. Eventually he was made the bishop of Antioch. Later Cyprian and Justina came to the attention of the "earl of that country" (so Caxton; comes or "count" in the Latin source; "prefect" in Ryan). He had them taken before him in shackles, beaten, scourged, and cast into a great vat of boiling pitch, wax, and tallow. When all this did not persuade them to return to the worship of the gods, he sent to Caesar for a judgment. The latter's order was to have the two beheaded.

JUSTINA AND PROSDOCIMUS OF PADUA

The Justina martyred in Padua was well renowned in late antiquity. In the 6th century the Paduans dedicated a church to her and she was among the virgin martyrs portrayed in the presbytery arch in the Euphrasian Basilica (at left) and in the procession of virgins in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo. In the 7th century, Venantius Fortunatus, writing in Gaul, urged travelers to Padua to visit her relics there.1

The Justina martyred in Padua was well renowned in late antiquity. In the 6th century the Paduans dedicated a church to her and she was among the virgin martyrs portrayed in the presbytery arch in the Euphrasian Basilica (at left) and in the procession of virgins in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo. In the 7th century, Venantius Fortunatus, writing in Gaul, urged travelers to Padua to visit her relics there.1

This saint is not, however, represented in the Golden Legend. A Latin life in the Acta Sanctorum says she was baptized in the first century by St. Prosdocimus. Later the story has her arrested at a marble bridge near Padua and brought before the Emperor, anachronistically named Maximian.2 When she refuses to sacrifice to Mars he orders her put to the sword in the Campus Martius, the very field that is today overlooked by her church, the Abbey of Santa Giustina.3

Although the instrument of death was a sword (in the Latin a gladius or short sword, as in these images), this Justina was not beheaded. Instead, she knelt down and the executioner stabbed her in the side, leaving her alive for an hour, during which she cast her eyes repeatedly to Heaven, praying that God would receive her soul.

NARRATIVE IMAGES

The images most obviously related to Justina of Padua are those at Santa Giustina in Padua. On the doors of the church we see modern reliefs of her baptism by Prosdocimus and her martyrdom:

|

|

Left: St. Prosdocimus baptizes Justina. The tablet held behind him reads Ego te baptizo, "I baptize you." The ewer becomes his attribute in other images.

Right: The martyrdom. The executioner stands behind Justina's shoulder as he prepares to plunge his gladius into her side, following the command of the Emperor seated on the left.

|

The stance of the executioner in the door relief and the plunging of the sword repeat the pattern in this painting of the Padua martyrdom.

The executioner stands behind the saint's shoulder and plunges the short sword into Justina's breast. Her eyes are already cast toward Heaven, as in the story. In the background is the marble bridge where she was arrested.

Clearly this is the Paduan Justina, yet the artist may have been influenced by images of the other Justina's passion. The men on the left wear "oriental" garb – turbans on the two white men and a Phrygian cap on the black executioner. The clothes of the young man on the right also seem more suitable for a comes than for an emperor.

And could the inclusion of an old man on the right be due to a portrayal of Cyprian in an Antiochene painting? In the portrait of Cyprian below the saint does indeed have a long gray beard like this man.

|

Attrib. Paolo Veronese, "The Martyrdom of St. Justina," Uffizi Gallery, Florence. (This image has a page of its own.)

|

Another painting of the execution at Padua is displayed inside Santa Giustina. This work also places the executioner behind the saint's shoulder, though in this case the sword is not visible.

As in the Uffizi painting Justina's eyes are cast up to Heaven, where indeed the angels have already been sent to answer her prayer and bring her the martyr's palm. As specified in the story, she is kneeling as she prays.

The church in the background is Santa Giustina itself, establishing the locale of the foreground as the Campus Martius (today the Prato della Valle).3

As in the other martyrdom painting, a few details hint at an Antiochene influence. The executioner is again an African, and the man in authority wearing the engraved breastplate at the far left is dressed more like the comes who condemned Justina of Antioch than the emperor who ordered the executions in Padua. Also, the shackles on the saint's wrists are from the Antiochene passion; there are none in the Paduan.

|

Paolo Veronese, The Martyrdom of St. Justina

|

|

The passion of Justina of Antioch is portrayed much less frequently. I have found none in my travels and only one online. The image on the right shows Justina and Cyprian in the vat of boiling fluids that Count Eutolmius has ordered for them. Cyprian wears a rather ill-fitting mitre. On the right, the bearded man in the fur robe and hat is most likely the Count.

The man in green assailed by flames on the far right is the pagan priest Athanasius, who thought he could show the power of the gods by entering the vat himself. Unfortunately, as soon as he approached the fire it leapt out and destroyed him.

The man in the red hat conversing with Eutolmius should be his cousin Terentius. Seeing that neither beatings nor fire could persuade the two Christians, he advised the Count to send to Caesar for a judgment.

Surprisingly, this image has no orientalizing touches, with the possible exception of the Count's round fur hat. This was part of the uniform of hussars in the 18th century, which is the probable era of the image. (The tricorne hats worn by the other two men are characteristic of the 18th century in the west.)

|

PORTRAITS

Andrea Mantegna, detail from the San Luca altarpiece, 1453

(View this image in full resolution)

|

Portraits of Justina of Padua tend to be like the one shown here on the left, with a palm branch and a short sword driven into the side of the chest.

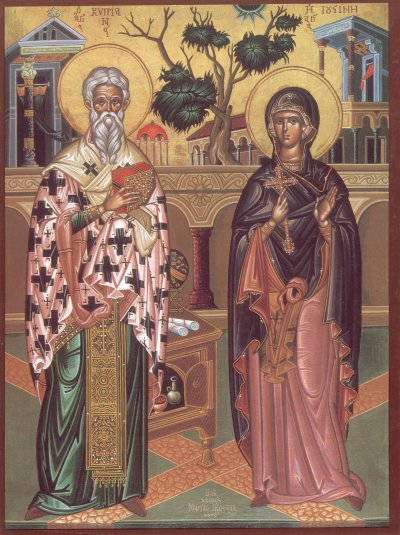

For portraits unquestionably of Justina of Antioch, I have found only some Eastern Orthodox icons, which typically put a cross in her hand. The cross refers to the episodes in which she made the sign of the cross as a defense against the blandishments of the demons. The icons pair this Justina with Cyprian, who is represented as an old man in episcopal vestments, as at right.

|

Romanian icon posted on Wikimedia Commons

|

|

In the West portraits of "Justina" sometimes seriously confuse the two saints. The image at right, for example, portrays three saints whose feast is on October 7: The soldier saints Serge and Bacchus, and Justina of Padua. The latter stands on a great demon, signifying her victory over the blandishments of the devils sent by Cyprian to tempt her. But it was Justina of Antioch who withstood those blandishments.

|

|

|

A statue in the west portal of the Franciscan Church in Vienna is identified by the photographer, a historian, as Justina of Padua. But in her left hand the saint holds a demon. This is most likely an allusion to the Antiochene story. Furthermore, the sword in her right hand is not the short gladius that killed Justina of Padua but more like the full-length sword that is an attribute of saints who were beheaded – for example St. Paul and St. Catherine of Alexandria. Thus it would be difficult to say with certainty which Justina is being portrayed.

|

|

|

Finally, a painting titled "Justina and the Unicorn" could go either way. According to Honorius of Autun a unicorn though wild will tamely place its head in the lap of a virgin, just as Christ prizes chastity and chose the Virgin Mary in the Incarnation (Sill 26-27). The unicorn here may therefore reference Justina of Antioch's steadfast defense of her chastity and perhaps her remark to her suitor (in the Latin version) that she is already wed to Christ ("De SS. Cypriano, Iustina et Theoctisto," 243).

However, it is a commonplace that virgin martyrs are brides of Christ of unimpeachable chastity, so Justina of Padua cannot really be ruled out. In this connection it may be noted that her hair is styled just like that of the Paduan saint in the Euphrasian basilica (see above).

The Web Gallery of Art suggests that the kneeling man is the donor.

(View this image in full resolution)

|

FEAST DAYS

-

September 26 for Cyprian and Justina of Antioch

-

October 7 for Justina and Prosdocimus of Padua

BIOGRAPHY

-

Justina of Antioch

-

Roman Martyrology for September 26: "In Nicomedia the

natal day

Not their birthday but the day they were "born again" into Heaven through martyrdom.

of the martyrs St. Cyprian and St. Justina, Virgin. Justina suffered torture for Christ, and the sorcerer Cyprian tried to drive her to madness with his magic arts. But she converted him to the Christian faith, and he gained martyrdom with her. Their bodies were thrown out for the wild animals, but a Christian sailor took possession of them and carried them to Rome. Afterwards they were

translated

Translation is a ceremony in which the body of a saint is taken from its resting place and interred in a more appropriate church or chapel.

to the Constantine Basilica and interred near the baptistery."

-

Golden Legend #142: html or pdf

-

"De SS. Cypriano, Iustina et Theoctisto" in Acta Sanctorum, Sept. vol. 7, 195-246.

-

John the Stylite's 8th-century vita is in Select Narratives, 185-203.

-

Justina of Padua

-

Roman Martyrology for October 7: "In Padua, St. Justina, Virgin and Martyr. She was baptized by blessed Prosdocimus, a disciple of St. Peter. For holding firmly to her faith in Christ, the Prefect Maximus ordered her pierced through with a sword. Thus she ascended to the Lord."

-

"De Sancta Iustina V. M." in Acta Sanctorum, Oct. vol. 3, 790-826.

-

Cyprian of Antioch

-

Metaphrastes' Greek Life of Cyprian of Antioch and Justina, with Latin translation: MPG, CXV, 844-82.

-

Prudentius, Peristephanon, Carmen XIII.

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, at Augusta University

HOME PAGE

1Butler IV, 450.

2The bridge is identified by the

Santa Giustina

Abbey's website as the Ponte Corvo. No first-century emperor

was named Maximian: see Andrew Wilson, "List

of Roman Emperors from Augustine to Constantine" (accessed

2013-11-02).

3The modern name for the

area overlooked by the abbey is the Prato della Valle. See Italian

Wikipedia, "Prato

della Valle."

The Justina martyred in Padua was well renowned in late antiquity. In the 6th century the Paduans dedicated a church to her and she was among the virgin martyrs portrayed in the presbytery arch in the Euphrasian Basilica (at left) and in the procession of virgins in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo. In the 7th century, Venantius Fortunatus, writing in Gaul, urged travelers to Padua to visit her relics there.1

The Justina martyred in Padua was well renowned in late antiquity. In the 6th century the Paduans dedicated a church to her and she was among the virgin martyrs portrayed in the presbytery arch in the Euphrasian Basilica (at left) and in the procession of virgins in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo. In the 7th century, Venantius Fortunatus, writing in Gaul, urged travelers to Padua to visit her relics there.1