In the first scene in the painting Asterius describes a judge who looks down severely from his throne on the blushing virgin, whom the artist has dressed in the pallium and dark tunic of a philosopher. In the next scene one executioner pulls her head back, a second forces her mouth open, and a third pulls out her teeth as blood flows from her mouth. In the third scene she is in prison, lifting her hands to a vision of the Cross. In the fourth she stands enveloped in flames, "rejoicing as she passes on to the blessed, incorporeal life."

Oddly, the subsequent iconography of Euphemia derives not from the ekphrasis but from an 8th-century passio Passio: An account of the suffering and death of a Christian martyr. by John the Stylite. The passio has some of the features that came to be familiar in accounts of virgin martyrs: speeches vindicating Christian monotheism, a named judge (in this case one Priscus) who reacts with growing wrath to the virgin's stubbornness, and a series of attempted executions or tortures miraculously averted. John's account puts Euphemia into a fire as the ekphrasis did, but for John this is just one of many attempts thwarted by divine intervention. At the end she is taken to the arena to be eaten by lions, but they simply lick her feet while one of them gently nips her shoulder. At that a voice from Heaven calls, "Ascend on high, O Euphemia!"2

Early in the 7th century the Emperor Heraclius removed the sarcophagus to Constantinople, lest it fall into the hands of the advancing Persians. But in the mid-8th century it was tossed into the sea by Iconoclasts. Those rejecting veneration of religious images and relics of saints. Then, according to texts collected in the Acta Sanctorum, God let it float safely to the island of Lemnos, whence it was returned to Constantinople after Iconoclasm had been suppressed.3

(See the description page.)

PORTRAITS

In portraits the lion becomes one of Euphemia's attributes, as in the first image at right. That image also shows a sword stuck in her breast. This refers to the way the Golden Legend's version ends: The lions' gentleness enrages Priscus, so a bystander finally dispatches the saint by thrusting a sword into her breast. (Death by the sword is a common trope in virgin-martyr stories, as is another feature of the Golden Legend's account, sexual humiliation.)No extant image has Euphemia in the philosopher's tunic and pallium mentioned in Asterius's ekphrasis. In 6th-century mosaics she wears the garb typical of female saints: a white veil, a gold-colored dalmatic with a jeweled or embroidered collar, and sometimes a jeweled coif (example). In later Orthodox icons she holds a cross and wears a maphorion A hooded upper garment often with a neck hole like the Virgin Mary's. In the West the garb varies.

NARRATIVE IMAGES

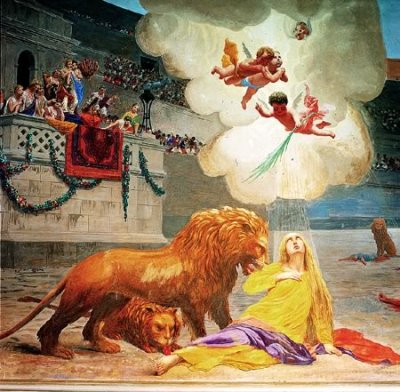

Narrative images are very rare. Jameson's 1879 survey of Euphemia's iconography discovered none at all, but in 1935 a photographer found a fresco series based on John the Stylite's account in the ruins of a church in Istanbul.4 The lions episode is pictured in a Croatian cathedral (the second picture at right) and in this stained glass window in Milan.Another narrative (or not-quite narrative) image is the ceiling fresco at Sant'Eufemia in Venice (third picture at right). It shows the saint ascending to Heaven from a place of martyrdom, but the person being slain in that place is someone else, a man who lifts his hand with the index and middle fingers raised to affirm the doctrine that there are two natures in Christ, human and divine. It was at Euphemia's church in Chalcedon that an Ecumenical Council reaffirmed this doctrine in 451 and condemned the "Monophysite" alternative that Christ had only a divine nature. According to legend, the two doctrines were written on two booklets and placed on Euphemia's breast in her sarcophagus; after three days of fasting and prayer the Monophysite booklet was found at the saint's feet and the Orthodox one in her right hand. During the ensuing centuries as controversy continued between Monophysites and Orthodox believers many churches along the Adriatic coast were consecrated to St. Euphemia as a way of declaring which side they were on. The Venice church was one of them.5

The Golden Legend claims that Ambrose of Milan (340-397) wrote in a "Preface" that Euphemia "was plucked unhurt from the fiery furnace" and then thrown to the "wild beasts," who "turned gentle and bent their heads."6 This seems unlikely, as these details reflect the account in John the Stylite and are at variance with what the Chalcedonians probably knew about Euphemia's martyrdom.

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University. Revised 2015-11-01, 2016-12-28, 2017-05-14, 2017-12-19.

Mantegna's 1454 portrait of St. Euphemia, with the lion at her side and a sword in her breast. See the description page for details.

The martyrdom of St. Euphemia: painting in St. Euphemia's Basilica, Rovinj, Croatia (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Ceiling fresco in Sant'Eufemia Church, Venice. See the description page for details.

ATTRIBUTES

- Lion

- Sword in her breast

MORE IMAGES

- 6th century: Detail from the apse vault in the Euphrasian Basilica

- 6th century: Mosaic with St. Pelagia in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna

- 1717: Fresco by William Borremans in Palermo

DATES

- Feast day: September 16

- Died in 303 or 304

BIOGRAPHY

- Golden Legend #139

- John the Stylite's 8th-century vita is in Select Narratives, 149-167.

- Roman Breviary: English translation, IV, 560; Latin original, 1039.

- Bede's Martyrology: Acta Sanctorum, March vol. 2, xxx.

- Acta Sanctorum, September vol. 5, 252-84

- Metaphrastes' Greek Life of Euphemia with Latin translation: MPG, CXV, 731-32.

ALSO SEE

- Another woman named Euphemia is among The Virgin Martyrs of Apuleia.

NOTES

1 Acta Sanctorum, September vol. 5, 283-84. Jameson (II, 170-71) has a partial translation. The possibility of an eyewitness source is suggested by the painting's closeness in time and location to the actual events and also by the absence of any of the fanciful divine interventions common in later hagiography.

2 John the Stylite, Select Narratives, 149-167.

3 Acta Sanctorum, September vol. 5, 258-60. The texts say the body's restoration to Constantinople occurred during Irene's regency (780-97).

4 Jameson, II, 169-174 and especially 173. For the Istanbul discovery see "The Church of Hagia Euphemia" and "West Apse Frescoes."

5 For this explanation of the fresco we are indebted to Sig.ra Maria Urbani de Gheltof Stradella, the historian of the Chiesa di Sant'Eufemia in Giudecca, Venice. For the theology involved, see the Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. "Council of Chalcedon." For the miracle of the booklets, see Acta Sanctorum, September vol. 5, 257.

6 Ryan, II, 183.