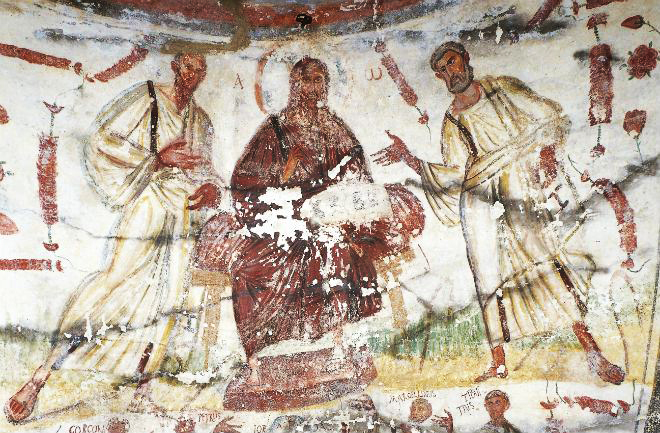

Starting in the 4th century, Christian art adapted the iconographic "vocabulary" used in images of the Emperor and his court to portray Christ as "King of Kings and Lord of Lords" (Revelation 19:16). Like a Roman emperor he was pictured on a throne flanked by "courtiers" — Peter and Paul, and often a number of others (example). In some images his hair and beard were modeled on portraits of emperors, which in turn had been based on statues of Jupiter (example). Sometimes the "throne" was a globe to represent the universe that he rules (example). This too was taken from imperial iconography.1

In these images Christ and his saints wore the garb of a Roman senator: a toga hanging from the left shoulder over a "dalmatic," which was a sleeved tunic with two vertical stripes.

Unlike the imperial portraits, Christ typically holds a scroll or book in his left hand and blesses the viewer with his right. In later images he can be flanked by the symbols of the four evangelists (example) or by various other saints. He is also enthroned in Last Judgment images from at least the 6th century (example).

By at least the late 5th century this iconographic type had diffused as far as Milan (example) and Alexandria, and even to an Arian facility in Ravenna. Later versions will have the image in a mandorla or circle (example). After the 12th century it became less common in the West, where images of the Madonna Enthroned gained popularity. (An important exception is the apse mosaic at St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome.)

In some cases, Christ was represented symbolically by an enthroned cross (example). In this apse from the 11th or 12th century, he is represented by both the cross and his own face. In later images angels are added to the entourage (as in the image above) or replace the saints entirely (example).

Another early type had Christ treading on a lion and a serpent (example), reflecting Psalm 90:13 (Vulgate), "Thou shalt walk upon the asp and the basilisk: and thou shalt trample under foot the lion and the dragon."

Two-dimensional Christ Enthroned images invariably put a crossed halo behind the figure's head, but in sculptural work a crown is used instead (example).

CHRIST PANTOCRATOR

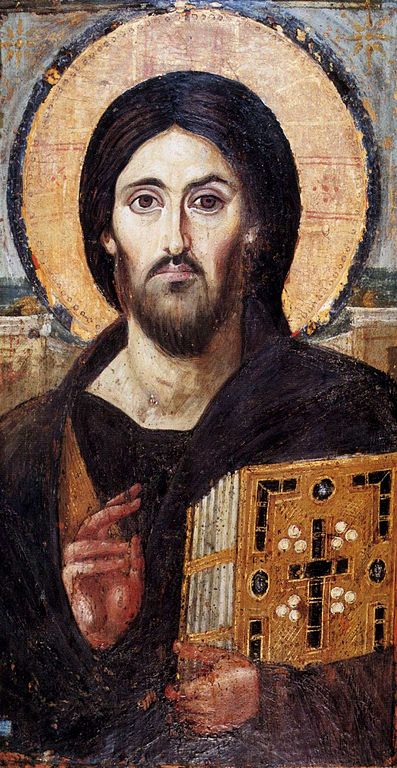

Eastern churches developed a similar iconographic type known as Christ Pantocrator. Portrayed half-height, Christ looks directly at the viewers and blesses them with his right hand. In his left he holds a book.1 The earliest extant example is the 6th-century St. Catherine's Pantocrator (second picture at right), but it may have been based on earlier works that disappeared during the Iconoclast ascendancy (Chatzidakis, 202-204).

The Christ Pantocrator became a common feature of Eastern apse mosaics (example). In Russia a version with a full-height Christ was adopted by iconographers in the 12th and 13th centuries for use on the iconostasis (example).2

THE BLESSING GESTURE

In the St. Catherine's icon, as in several of the images cited above, Christ blesses the viewer with the thumb of the right hand touching the fourth finger (the one next to the pinky). In the sarcophagus fragment mentioned above, the fingers also seem to be arranged this way. A number of sites on the web say this began as an oratorical gesture, but I have not found it in any statues of Roman orators, nor is it mentioned in Quintilian's extensive survey of hand gestures.3 Whatever the origin, Orthodox believers see it as a way of forming the letters IC XC, the monogram of Jesus Christ,4 and in the East it is the traditional way of picturing the fingers in Christ's blessing.

In the West a tradition gradually developed of picturing the blessing hand with the fourth and pinky fingers curved down and the thumb and other fingers pointed up, as in the third picture at right. This is seen as early as the 6th century in this mosaic. In the 9th century Leo IV required priests to bless the chalice and host during Mass with their fingers held this way, "by which the Trinity is symbolized." By the 11th century it became the configuration that western Christians used when making the sign of the cross on themselves. After the Middle Ages, the open hand was more common for the sign of the cross, but the art continued to picture Christ's blessing with the thumb and two fingers raised (example).5

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University.

HOME PAGE

Christ Enthroned (12th century), The Palatine Chapel, Palermo, Sicily. See the description page.

OTHER IMAGES

Catacombs painting, 4th century – See the description page

The earliest known Christ Pantocrator, in St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai – See the description page

Enthroned on a blue disc representing his reign over the universe, Christ blesses the viewer with what was to become the standard blessing gesture in the West. – See the description page

MORE IMAGES

- 4th or 5th century: In the Euphrasian Basilica, a fresco of Christ enthroned with a book on his knee and flanked by women saints and another nearby with Christ flanked by St. John the Evangelist and one other saint.

- 5th century: Christ with the 24 elders.

- 6th century: The enthroned Christ receives the martyrs' crowns.

- 6th century: Christ Pantocrator with the Evangelists above the main apse at San Vitale, Ravenna.

- 6th century: Small mosaic image of Christ blessing the congregation above the apse mosaic of the Transfiguration at Sant'Apollinare in Classe.

- 6th-8th century: Christ enthroned is the central image in the apse mosaic at the Ambrosian Basilica in Milan.

- 7th century: Christ stands and gestures welcome from the apse at the church of SS. Cosmas and Damian, Rome.

- 10th century: Whalebone carving of Christ enthroned with book and blessing.

- 10th or 11th century: Apse of a Carolingian-era church in Switzerland with an early example of the use of a mandorla.

- Circa 1050: Apse fresco in an Austrian church, also with a mandorla.

- 11th century (?): Spanish tympanum: A crowned Christ stands and blesses the viewer.

- 12th century (?): A mosaic in St. Mark's, Venice, pictures Christ as "King of Kings" (Revelation 19:16) leading his host against the Beast.

- 12th century: A fresco using a mandorla in Salamanca's old cathedral.

- 12th century: Pantocrator mosaic in the cathedral apse in Cefalù, Sicily.

- 12th century: Tympanum in Assisi, Christ in a clipeus flanked by St. Rufinus and the Virgin Lactans.

- Second half of the 12th century: From Rome, a Romanesque treatment of the Christ Pantocrator.

- 12th or 13th century: Mosaic above the apsidal arch at San Clemente, Rome.

- 13th century: A rare case of an enthroned Christ blessing with only index and middle fingers pointing upward.

- 1285: A fresco in Florence attributed to Duccio di Buoninsegna.

- 13th or 14th century: Tympanum in Léon, Spain, with enthroned Christ and the four evangelists.

- 1291: In the apse at Santa Maria in Trastevere Christ shares his throne with Maria/Ecclesia.

- 1354-57: Orcagna's Strozzi Altarpiece.

- 1512-31: This relief sculpture in Oviedo is an exception to the rule that Christ in Majesty figures will have halos in two-dimensional works but crowns in sculptures.

- 1688: In a triangle flanked by SS. Peter and Clement in a dome fresco in Seville.

- 1919: People from the world over approach the enthroned Sacred Heart.

ALSO SEE

NOTES

1 The Greek word Pantocrator means "Lord of All." It renders Hebrew words for God 58 times in the

Septuagint, nine times in Revelation, and once in 2 Corinthians. See 2 Corinthians 6:18, Revelation 1:8, 4:8, 11:17, 15:3, 16:7, 16:14, 19:6, 19:15, 21:22. For the Old Testament passages, see this page.

2 Tradigo, 230.

3 Institutes of Oratory, XI, iii, 92-104.

4 Tradigo, 244. In the several mosaics of Christ at Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio, Palermo he makes this gesture, It is also made by Gabriel annunciant and by a number of saints. A few of these point the gesture at themselves. Mark points it at his gospel while holding his pen. Other saints bless with the thumb touching the middle and fourth fingers, holding the index and pinky fingers straight up. St. Andrew points this gesture at his cross; St. Thomas points it at himselv. See the plates in Kitzinger. Thus, except in picturing Christ's fingers, the Ammiraglio mosaicists seem not to have sought for any kind of consistency in the blessing gestures.

5 Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. "Sign of the Cross."