THE "ORIENTAL" TYPE

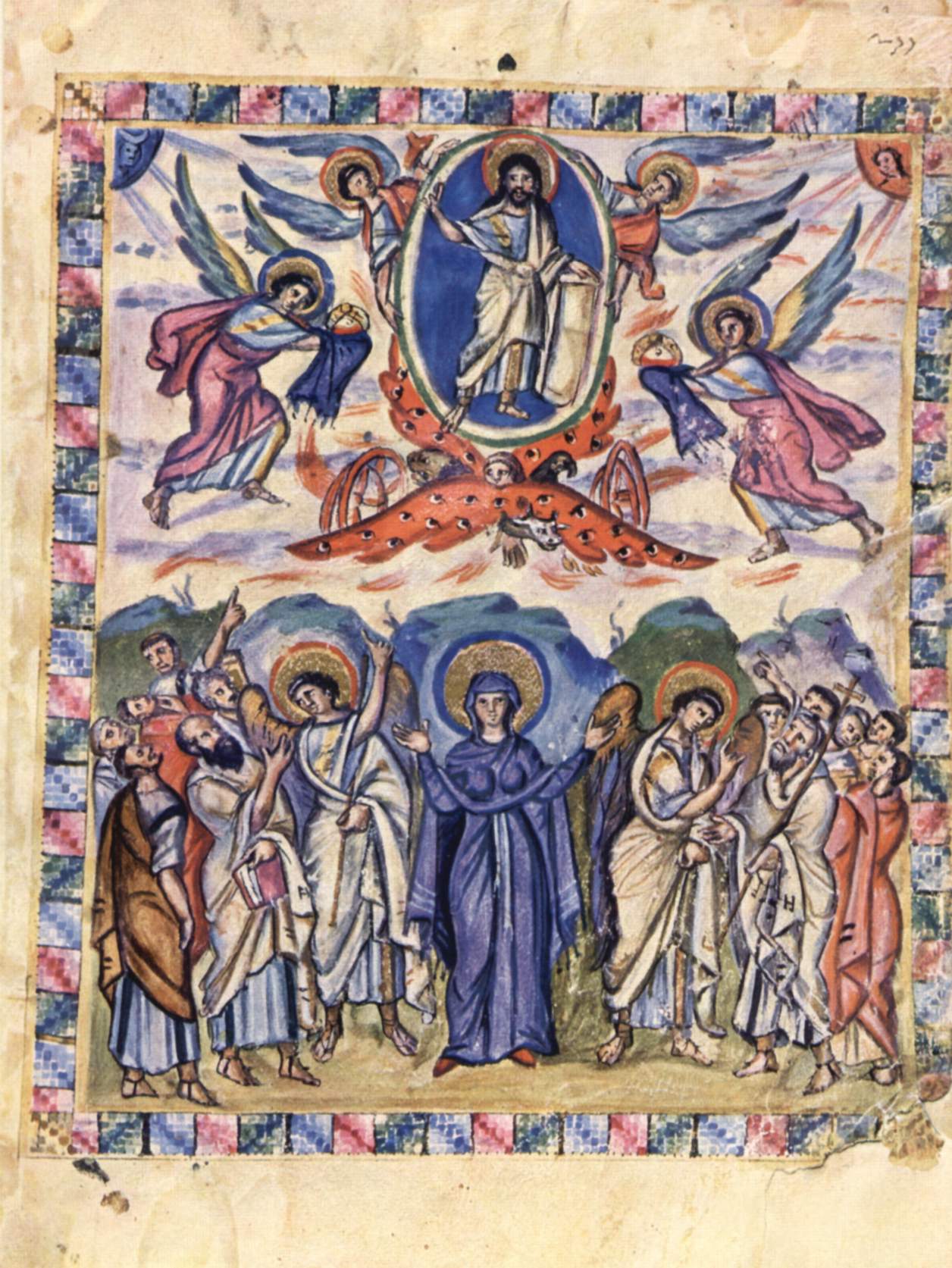

The earliest known example of the Oriental image type is the illustration in the first picture at right, from a Syriac gospel book. It ignores the testimony of scripture and the apocrypha that only the eleven disciples were present, adding St. Paul and the Virgin Mary, who stands orant in the center beneath the images surrounding Christ.2 This image type draws on Ezekiel 1, which was read in the Syriac liturgy for the feast of the Ascension.3 In that chapter, Ezekiel sees "the likeness of a throne…and upon the likeness of the throne, was a likeness as of the appearance of a man above upon it" (1:28), attended by four Seraphim who move on four wheels that "sparkled like topaz" (1:15-16) In 2:1 he concludes, "This was the vision of the likeness of the glory of the Lord." In the manuscript illustration the "likeness of the glory of the Lord" is Christ, attended by four angels and standing in a wheeled mandorla supported by a Seraph. His left hand holds a large scroll, referencing the one that Ezekiel is told to eat (2:8-9). From the bottom of this complex image a hand reaches down toward Mary, identifying her with the prophet, of whom Ezekiel 1:3 says, "the hand of the Lord was there upon him [Latin super eum]."Scholars have attributed the prominence of Mary in this image type to "an intention to give the scene a subsidiary meaning as a glorification of the Virgin."4 But more likely she and the twelve men flanking her represent the Church whom Christ has just appointed to "be my witnesses in Jerusalem, throughout Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth."5 The Church thus becomes a prophet like Ezekiel, who had been told, "I send thee to the children of Israel, to a rebellious people, that hath revolted from me" (2:3).

In some versions of the Oriental type a dove descends upon the head of Mary. In the former dispensation Ezekiel had had only the injunction to proceed bravely on his own: "Do not fear, even though there are briers and thorns and you sit among scorpions" (Ezekiel 2:6). But now at the Ascension Christ promises the disciples that "you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes upon you" (Acts 1:8).

Images of this type always put the actual figure of Christ inside a mandorla. In most of them he blesses the viewer with his right hand as he ascends, following Luke 24:50, and in many his other hand will hold a scroll or book. Many will have him enthroned, as in Ezekiel 1:26. In the Romanesque and later medieval periods the mandorla may be retained but the iconography is gradually simplified and focuses more on the glorification of Christ. This 12th-century relief in Rome excises Mary and the disciples and has little connection to Ezekiel beyond the angels and the stylized throne, and this example from the 13th leaves out even the angels.

Dewald chose the term "Oriental" because to his mind "the unreal and abstract treatment gives the scene a mystic character consistent with Oriental habits of thought" (279). This is nonsense, but in view of the connection with Syriac art and liturgy I have chosen to retain the term here.

THE "HELLENISTIC" TYPE

The "Hellenistic" image type goes back at least to the end of the 4th century (Dewald, 279). The second picture at right is an example. In contrast to the symbolism and ecclesiology of the Oriental type, it presents only a few disciples reacting in awe as Christ ascends a mountain, reaching out toward a hand that emerges from a cloud. The mountain alludes to Psalm 23:3-4, which was read in the Ascension liturgy in western churches: "Who shall ascend into the mountain of the Lord: or who shall stand in his holy place? The innocent in hands, and clean of heart, who hath not taken his soul in vain, nor sworn deceitfully to his neighbour." In ascending the mountain, in other words, Christ is modeling the way to salvation for every person who will follow him in "cleanness of heart."Dewald considered this image type "Hellenistic" because it was "realistic" in the way it represents the figures and their setting, like the classical art of Greece and Rome. It was less influential than the "Oriental" and is very rare in the West after the twelfth century, although Giotto did adapt it for his Ascension frescoes at Assisi and in the Scrovegni Chapel, and it may have influenced the composing of the Alleluia verse in medieval Ascension liturgies: Dominus in Sina in sancto ascendens in altum captivam duxit captivitatem, "the Lord leads captivity captive, climbing on high to his holy place on Sinai."6 A third image type, which Dewald calls "Gothic," can be seen in many Ascensions of the late 12th century through the 15th. In this type one sees only Christ's feet and the hem of his garment. The rest is hidden in the cloud that "received him out of their sight" (Acts 1:9). Usually the disciples are looking up at their disappearing Lord. The third picture at right is an example. As in most of the "Oriental" images, the feet are bare. Mary is often included, either centered or displaced to the left side (example).

Desham explains the disappearing feet as a way of leading the viewer to vicarious participation in the event, which was typical of 11th-century art, commentaries, and liturgical innovations. A number of commentators held that the feet symbolize Christ's humanity, which the faithful will continue to have with them in the form of the Eucharist and the visible Church, while the cloud represents his divinity, which they will see fully only in Heaven.7

LATER DEVELOPMENTS IN THE WEST

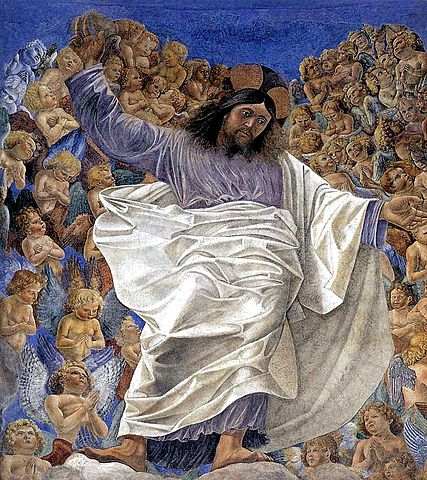

In the Renaissance and later, Ascension images emphasize more and more the "glorification" of the risen Christ that is at the core of the Christian message.8 A few works do this simply by showing rays of light emanating from the figure of Christ (example). But mostly the art moves toward an Ascension that places Christ in a surround of angels and brilliant light. The first step appears to have been taken by Melozzo da Forlì in a 15th-century Ascension fresco of which only fragments now remain. In one fragment the ascending Christ stands on a cloud and is surrounded by angels:

(Source Wikimedia Commons)

Source: this page at Wikimedia Commons.

See the description page.

Prepared in 2016 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University.

HOME PAGE

The Ascension: From the Rabula Gospels, 6th century. (See the description page)

Ivory plaque, circa 400 (See the description page)

Early 15th-century manuscript illustration (See the description page)

MORE IMAGES

- Circa 720-970: Byzantine ivory carving with Mary dressed as a priest.

- 12th century: A fresco of the "Oriental" type in Salamanca's Old Cathedral.

- 12th or 13th century: The Gothic-type Ascension panel in a window in Canterbury is accompanied by four secondary images of Old Testament events thought to prefigure the Ascension.

- 1175-1200: The Ascension Cupola over the crossing in St. Mark's Basilica, Venice.

- Early 14th century: In the shallow space of this tympanum the angels lift Christ up in a broad cloth rather than a mandorla.

- 14th century (est.): A "disappearing feet" Ascension in a stained glass window in Vienna.

- 1344: Detail from Guariento di Arpo's Coronation of the Virgin altarpiece.

- 15th century: Barnaba da Modena, The Ascension.

- 15th century: Detail from the New Testament frescos at Pomposa Abbey, Italy.

- Early 16th century: A "disappearing feet" Ascension in Oviedo, Spain.

- 16th century: An Ascension image associating the feast with the city of Venice.

- 1579-81: Tintoretto's Ascension is a late example of the "Climbing to Heaven" type and an early example of the emphasis on glorification by means of a surround of light and angels.

- 19th century: This relief replacing the top of a tympanum damaged in the French Revolution keeps to the medieval style but lacks some of the traditional iconography.

- 19th/20th century: An apse painting in a traditional Canadian church, with the latter-day use of light rays to express Christ's glorification.

MEDIEVAL COMMENTARY

NOTES

1 Dewald, 278.79.

2 It is clear that in Mark and Luke the authors have no sense that Mary was present. Luke 24:50-51 says nothing about any women in the group that saw the Ascension. Mark's narrative of the event begins at Mark 16:14, where "the eleven were at table" and continues without a break until Jesus "was taken up into Heaven" at Mark 16:19. The Gospel of Nicodemus (XVI, 5) also speaks of Jesus ascending "as he taught his eleven disciples." Most significantly, the angel in Acts 9:11 addresses those disciples as "you men of Galilee" (Greek Ἄνδρες, Latin viri).

3 Kessler, Introduction to "The Christian Realm: Narrative Representations," in Weitzmann, 454.

4 Dewald, ibid., 287. Deshman (525) suggests that Mary's presence in this image type can reflect physically the supernatural enlightenment that Christ's divinity had shed on her and all humankind in the Incarnation."

5 Acts 1:8, c.f. Matthew 28:10, Luke 24:47-48. For the identification of Mary with the Church, see my note on Maria Ecclesia in the "Ecclesia: The Church."

6 Missale Romanum, 292-93. Sarum Missal, 412-13.

7 Deshman, 526-29, 536-7.

8 See Acts 3:13, "The God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, the God of our fathers, hath glorified his Son Jesus, whom you indeed delivered up and denied before the face of Pilate, when he judged he should be released" and Romans 8:17-18, "…if we suffer with him, that we may be also glorified with him. For I reckon that the sufferings of this time are not worthy to be compared with the glory to come, that shall be revealed in us."