NARRATIVE IMAGES

The Golden Legend's life of Anthony begins with the brutal torments visited upon him by demons, and these are a favorite subject in the art (image). Narrative images also draw on episodes from the Legend's lives of Anthony and St. Paul the Hermit. The former famously undertook a difficult journey (image) to visit the latter and learn from his wisdom (image). While he was visiting, the two were fed by a raven that brought one loaf of bread for each of them, as in this panel from Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece. On a second visit, St. Anthony found the old hermit dead. Lacking a shovel to bury him, he managed to get him into the ground with the help of some passing lions (image).PORTRAITS

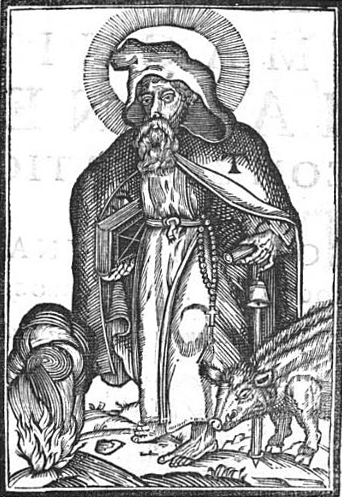

Anthony's attributes are well summarized in a 17th century commentary by Théophile Raynaud: "St. Anthony is portrayed as a venerable old man with a long beard wearing a monk's habit with a T printed on the left side of the hood, holding a book and staff in one hand and a bell in the other, and having a pig at his feet. Also a brightly burning fire."1 (At right is the frontispiece from Raynaud's work.)The Habit and the Pig

As for the habit and pig, in the middle ages Anthony was the patron of a monastic order known as the Hospitallers of St. Anthony, who made a specialty of treating diseases of the poor in medieval cities. These monks wore a black habit and were authorized to support their charities by raising swine.2 For this reason, Anthony is often depicted in the same black habit and with a pig as his attribute, as in the first picture at right.Some images emphasize his intercessions on behalf of those suffering from epidemic diseases. In a Tintoretto painting commissioned by the Doge Nicolò da Ponte, the latter prays to Anthony for relief from the plague of 1575-77; Anthony in turn addresses the Child Jesus, who directs his right hand in blessing over the city of Venice. The saint frequently appears with St. Catherine (example), who as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers protects against sudden death – as does St. Barbara, with whom he is grouped in a 1523 altarpiece by Jacopo Palma il Vecchio. Also relevant to Anthony's role as health-bringer may be Giordano's Birth of the Virgin, in the lower half of which the figure of Anthony mediates between the wizened parents in the dim background and the plump, pink, and fully illuminated baby in the arms of a correspondingly youthful midwife.

Raynaud, uncomfortable with the pig symbol for a holy saint and mindful that Anthony was a vegetarian, suggests that placing the animal at his feet signifies either his efforts to feed the poor or the subjugation of "the three porcine kinds of men: ...pagans, heretics, and Christian voluptuaries," citing numerous commentaries and biblical texts that use pigs as a pejorative symbol (32-41). However, it must be noted that the images typically do not show the pig under the saint's feet or portray the animal as uncomfortable with its setting. (A possible exception shows Anthony standing on a demon that could be considered pig-like and impaling the fiend with his staff.) By contrast, evil creatures vanquished at the feet of other saints are usually shown in some sort of discontent, if not torment. (See examples with SS. Bartholomew, Margaret, Vincent, and Thomas Aquinas.) On the other hand, despite the Bible's consistently negative figures of speech involving dogs,3 those at the feet of SS. Roch and Dominic are unambiguously positive in their signification. Thus, the position of St. Anthony's pig is by no means a necessary sign that it represents enemies of the Christian Church.

The Bell

Bells were used to call swine in at the end of the day, so a single bell or a pair (example) entered the canon of the saint's attributes. Raynaud notes that many writers have taken the bell to signify the saint's guardianship of swine and other beasts but again protests the unsuitability of such a signification to a holy saint (52-7).The Staff and the Tau

As in the frontispiece at right, the staff almost always has a tau-shaped top (another example; an exception). The staff itself may be the oldest of the Antonine attributes. Raynaud cites one ancient source as saying the staff was the symbol of monasticism in Egypt and another as relating the symbol to the monks' physical journey into the desert and spiritual journey in "seceding from this world."4 For the tau top on the staff, he cites the prestigious contemporary scholars Molanus (Jan Vermeulen) and Jacob Gretser, who agree that the T shape was the way Egyptians represented the cross of Christ in Anthony's time, and he reminds the reader of the many times the cross protected the saint from demons who assailed him in the desert (59). We see the cross doing just that in the second picture on the right: Anthony sits blissfully in the foreground with his book and pig while a gleaming cross separates him from monstrous figures in the background. In memory of the tau-top staff, the Antonine monks adopted the T on their hood from their founding at the end of the 11th century, and that is why it is sometimes placed retrospectively on the saint's hood in his images, as at right and in the Tintoretto painting and this example (Raynaud 57).Prayer Beads

In the Orsi painting at right the cross also figures on a pair of beads that hangs from Anthony's left wrist. We also see him with prayer beads in a fresco in Urbino.Hair and Beard

Anthony's "venerable old" age is most often expressed by some degree of baldness, usually affecting the top of the skull but not the sides of the head (example) but sometimes leaving a bit of hair on top (example). The head is only rarely covered by a hat (example) or abbatial mitre (example). The saint's beard is almost always long, forked, and white (example).The Flames

The brightly burning fire may be anywhere in the portrait: sometimes on the saint's hand (example), sometimes atop the staff (example), or even consuming the hand of a diseased supplicant, as in one 16th-century woodcut.5 Butler and Duchet-Suchaux explain the flame as related to "St. Anthony's Fire," the disease erysipelas, outbreaks of which were said to be relieved by prayer to this saint and invocation of his relics.6 Raynaud also relates it to erysipelas, from which God has granted Anthony to be a defender, but also to his commission to defend others from the eternal fires of Hell and himself as a monk from the "profane fires of lust" (3-32).This latter signification is supported by many episodes involving fire in the hagiography. In one episode in the Golden Legend, St. Anthony throws into the fire a heap of gold that the devil had set in his path as a temptation (image). In another, and also in one from Athanasius' Life, a silver platter appearing before the saint vanishes in a puff of smoke when he dismisses it as another diabolical trick. In Athanasius, fire is a continually repeated theme, referring variously to lust, worldly desires, Satan's breath, and "the fire prepared for the demons who attempt to terrify men with those flames in which they themselves will be burned" (¶ 24).

The Book

Finally, the book (in the pictures at right and this example) is a more noteworthy attribute than one might think. Books appear in the images of a great many saints, signifying their having read or written religious works. But after taking up the eremetic life St. Anthony eschewed books, relying on his memory of sacred literature previously read.7 Raynaud notes this fact and explains the book as bearing several significations (41-45).First, the saint serves mankind as a "book" from which one can learn the Christian virtues. Second, we are reminded of his continually reciting the prayers learned from books seen in his early life.

Thirdly, the book in Anthony's hand recalls the portraiture of the ancient philosophers and shows he is their Christian counterpart. Thus Jacopo Bassano uses him to exemplify the contemplative life in St. Martin and the Poor Man with St. Anthony Abbot, St. Martin being the contrastive exemplar of the active life.

Raynaud's final point is that without actual books in his cell Anthony was better able to contemplate the "book of God's creation" in the world around him.

Medicinal Plants

In the Grünewald panel mentioned above, the plants at the feet of the two saints are the very ones used by the Antonine friars to treat erysipelas. (See this detail at the base of the panel.) Similarly, in this portrait of Anthony the plants at his feet appear to be ribwort plantain, which relieves the burning sensation caused by the disease.8With St. Martin of Tours

St. Anthony is consistently paired with St. Martin of Tours in the works of Jacopo Bassano. In 1542 the two flank the throne in his Virgin and Child with the Saints Martin of Tours and Anthony the Great,9 in 1568 they are in the lower left of the Adoration of the Shepherds, in 1578 in the lower right of the Paradiso, and in the 1580s in St. Martin and the Poor Man with St. Anthony Abbot. Most likely this pairing was intended to reflect the "active" and "contemplative" ways of living the gospel, which were first distinguished by Gregory the Great in the 6th century and later became a common medieval trope.10

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University.

HOME PAGE

Frontispiece to Raynaud's In Symbolicam S. Antonii magni Imaginem commentatio

Lelio Orsi, The Temptation of St. Anthony, 1570s (See the description page.)

St. Anthony portrayed in the Orthodox style, Monreale Cathedral, 12th-13th century (See the description page)

MORE IMAGES

- 1340: Sassetta and his workshop, The Life of St. Anthony.

- 1390s: Cenni di Francesco's Coronation of the Virgin altarpiece has a portrait of Anthony Abbot among the other saints on the right wing and a panel with the Temptation of St. Anthony on the predella.

- 1600: Giandomenico Tiepolo's Liberation of St. Anthony shows the saint rescued by angels after his battle with the demons.

ATTRIBUTES

- Pig, bell

- Tau-top staff

- Black habit of the Antonine order, often with a T on it

- Fire

DATES

- Feast day: January 17

- Lived from 261-356

NAMES

- Also known as St. Anthony of Egypt, St. Anthony the Great, or St. Anthony of the Desert.

BIOGRAPHY

- Golden Legend #21: html or pdf

- St. Athanasius, Life of Saint Anthony: html or pdf. Parts of this Life also appear in Stouck, 57-82, and Head, 7-31.

- Golden Legend #15 (Paul the Hermit): html or pdf

- Anthony's vita in The Roman Breviary: English translation, I, 687-88; Latin original, 793-94

- Jerome's Life of Paul the Hermit

- Various lives of St. Anthony are in Acta Sanctorum, January vol. 2, 107-162.

ALSO SEE

NOTES

1 Raynaud, 3. (Effingitur enim S. Antonius specie venerabilis senis, promissa barba, monastico opertus amictu, cui ad pallioli latus sinistrum impressa figura T., manu una librum tenens, & implicitum baculum, altera campanulam: ad pedes habens hinc suem, inde ignem luculentum).

2 Hayum 154, footnote 5.

3 For all instances of the word "dog" in scripture see the Bible Gateway engine. All are negative except for Tobit 6:1 and 11:19 (Vulgate, Douay), where an actual tail-wagging dog is companion to the travelers Tobias and Raphael.

4 Raynaud 46. The two ancient writers are, respectively, SS. Isidore of Pelusium (died 449 or 436) and John Cassian (360-435). The latter, according to Raynaud, also related the monastic staff to the one that Elisha found ineffective in reviving the son of the Shunammite woman, in its failure being a type of the Law, which cannot give life (see 2 Kings 4:8-37). This may explain the pairing of St. Anthony with Elisha ("Santus Elixeo") in a fresco in the Church of St. Roch, Draguc, Croatia.

5 Reprinted in Hayum, 22.

6 Duchet-Suchaux, 39; Butler, I, 109. Also see the account of Anthony's miracles during an outbreak of erysipelas in Flanders in Acta Sanctorum January vol. 2, 156f.

7 Athanasius, ibid., ¶ 3. The ownership of books, or of anything else, was discountenanced by the Desert Fathers. See Waddell 89 and 125-26.

8 Hayum, 23-24. Ballard 2009.

9 "Virgin and Child with the Saints Martin of Tours and Anthony the Great" (1542-43). The painting is in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich. A photograph is available at this page on Wikimedia Commons (retrieved 2022-06-11).

10 Gregory explains what constitute the active and contemplative lives in his Homilies on Ezekiel, II, ii, 7-8 (Migne, Pat. Lat. LXXVI, 952-57). There is a new English translation of the homilies (Etna, California: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 1990), but I have not yet read it. The subject is also studied in Aquinas's Summa Theologiae, Second part of Part II, questions 179-182. Online at this page at New Advent. For a history of the concept, see Sister Mary Elizabeth Mason, Active Life and Contemplative Life: A Study of the Concepts from Plato to the Present (Online at Marquette University Press Publications, 1961).