PORTRAITS

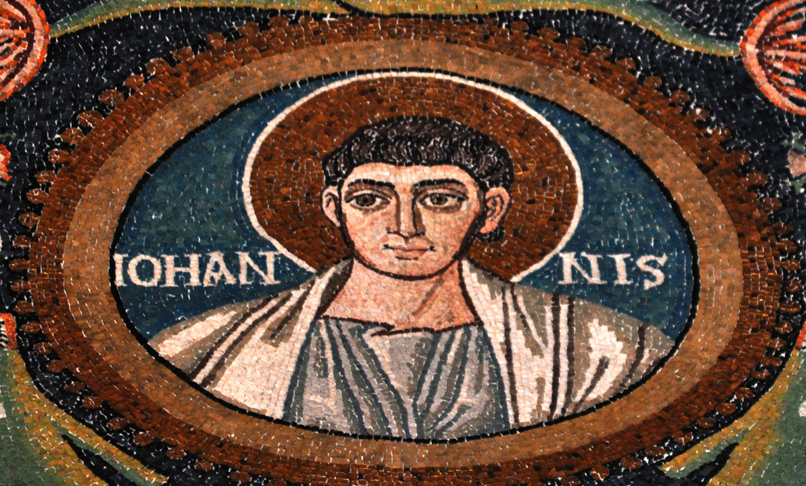

In solo portraits, John's attribute may instead be a cup or chalice with a snake in it (example). This refers to a story recounted in the Golden Legend in which a pagan priest challenges John to drink a cup of poison without being harmed. John not only survives but resurrects two men who had died from the very poison given to him (image).3 In the Latin, the poison is venenum, which also means snake venom – a boon to artists, who can indicate the deadly contents by placing a snake in the cup. Molanus says the cup is also partly a reference to the words of Christ in Matthew 20:23, "You all will drink my cup" – that is, the death that he will endure on the Cross (III, lviii: p. 399). This is the point of one image in Sant'Agnese in Agone, Rome, where an angel presents a cup to John.In most portraits and other images in the West, St. John is a young person with either a short beard or none at all (example). This may be due to the way the gospels always put his name second after his brother James, as if he were the younger of the two. Molanus attributes the tradition partly to the fact that "he was an adolescent at the time of the Last Supper and partly because of his perpetual virginity" (ibid.). The Golden Legend also mentions the tradition about John's virginity and attributes it to St. Jerome.

In illustrations of the legendary material, however, the saint may sometimes be pictured as an older person with a white beard (example), especially in the East, where his white or grizzled beard will be bifurcated and he will have a high forehead (example).

NARRATIVE IMAGES

For images of John as he appears in gospel episodes, see the pages for St. James the Greater, the Transfiguration, the Last Supper, and the Crucifixion.Cartlidge and Elliott (187-89) suggest that the few images of Christ calling John away from a proposed marriage may be following a now-lost episode in the Acts of John.

The legendary material usually recounts the ancient story that John was evangelizing successfully in Ephesus when the Emperor Domitian summoned him to Rome and had him cast into a vat of boiling oil at the Latin Gate. This was another popular subject for paintings. They normally picture officials and soldiers overseeing the proceedings, a servant stoking the fire below the cauldron, and some sort of architectural backgound to suggest the Latin Gate (example). The saint was unharmed by the boiling oil, so the emperor exiled him to the island of Patmos, where he penned the Book of Revelation.

Images of John on Patmos mostly follow the pattern of the third picture at right. In the lower half of the image he sits on an island with pen and book, gazing to the upper left, where the vision revealed to him is symbolized by heavenly light or by some image drawn from the Book of Revelation itself (example). Some images will also include the angel mentioned in Revelation 1:1. Others add an eagle, John's attribute. Eastern versions will also include his assistant Prochorus (example).

Upon his release from exile, John returns to Ephesus, where the Christian community is about to bury a woman of their number named Drusiana. She had always said she loved the saint and hoped she would get to see him again some day, so he restores her to life and she goes off to make him a meal (image). Other non-scriptural episodes in the legends include several depicted on the margins of a Crucifixion by Francesco Ghissi: the destruction of the Temple of Diana (story, image), his preaching and object lesson to Actius and Eugenius (story, image) and the raising of Satheus to life (story, image).

THE QUESTION OF JOHN'S "ASCENSION"

The 2nd-century Acts of John claims that at the end of his life John asked his disciples to dig a pit outside the gates of Ephesus. He then prayed a lengthy prayer, lay in the pit, and "gave up his spirit rejoicing." In Latin translations a great light appeared over the saint for an hour, and in some Greek recensions the disciples "brought a linen cloth and spread it upon him, and went into the city. And on the day following we went forth and found not his body, for it was translated by the power of our Lord." The Orthodox Church in America relates the same account on its web page for September 26, the Orthodox feast of the Repose of John the Theologian. The web page includes an icon showing the disciples laying the linen cloth over the body.The Latin versions of this story evolved through the years. The locale of the pit became the space in front of the altar in John's church, the "great light" temporarily blinded the congregation, and the "translation" was more explicitly a bodily ascension into Heaven. The 13th-century Early South English Legendary (416-17) compares John's ascension to the Virgin Mary's, adding that such a reward is suitable for virgins. In its original form the Golden Legend was more reticent about where the body went (Ryan, I, 55), and Caxton's translation says only God knows what really happened. But in medieval art there are no such doubts. Beginning at least with Giotto in 1315, the emphatically embodied saint floats up from the church into Heaven, where Jesus and the Apostles reach out to welcome him (example). In San Pietro, Venice, a painting that the church cagily labels "Saints John, Peter, and Paul" may in fact be picturing the ascension.

ST. JOHN AND ST. EDWARD THE CONFESSOR

The Legend also tells of an episode from the life of St. Edward the Confessor in which the king gave a valuable ring to a poor pilgrim who turned out to be St. John. Thus we see John with the king in an early 20th-century window in an English church.

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University. Revised 2017-01-11, 2017-11-22, 2018-03-30, 2020-05-05.

HOME PAGE

6th-century mosaic in Ravenna (See the description page)

9th-century ivory (See the description page)

St. John on Patmos, the eagle above his left shoulder (See the description page)

MORE IMAGES

- Mid-12th century: Byzantine-style portrait in the Church of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio ("The Martorana" in Palermo.

- 13th century (est.): A stained glass window with St. John and three other Apostles.

- 13th century (est.): The Apostles Window in Regensburg Cathedral, picturing the martyrdom of each Apostle.

- 1220-30: In this fresco St. John is pictured with two saints who wrote commentaries on his gospel.

- 1260-80: A manuscript illumination picturing John asleep on Jesus' chest at the Last Supper.

- 14th century: Portrait of St. John by Giusto de' Menabuoi.

- Early 14th century: St. John's portrait is among Aretino's panels of Apostles and saints in Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

- 1371: Unusually, the saint wears a long white beard in Giovanni Bonsi's Madonna Enthroned with Saints

- 1390s: A portrait of St. John that uses a book and pen as his attributes is included in the right wing of Cenni di Francesco's Coronation of the Virgin Altarpiece.

- 14th-15th century: A fresco tentatively identified as St. John the Evangelist.

- 15th century: In this portrait the chalice contains not snakes but a single winged dragon.

- 1465: Altar frontal with St. John and the Virgin Mary flanking the Man of Sorrows.

- 1475-80: The saint is pictured in the center of a composite stained glass window from England.

- 1480-90: Master of the Winkler Epitaph, St. John at the Latin Gate.

- 1513-14: With SS. Andrew and Jerome in the Costabili Polyptych

- 16th century: Marcello Venusti, The Martyrdom of St. John the Evangelist.

- 1520: Stained glass portrait of the saint with the chalice and serpent.

- 1725: John's youthful beauty in Balestra's painting of the episode of the boiling oil reflects the Golden Legend's comment that his immunity to the heat of the caldron was like his lifelong "alienation" from fleshly passions.

DATES

- December 27 is the main feast day for St. John.

- May 6 is the feast of "St. John at the Latin Gate," the place where he survived boiling in oil.

NAMES

- In the Orthodox churches he is St. John the Theologian.

BIOGRAPHY

- Golden Legend #9

- Golden Legend #69

- Acts of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian, in Schaff

- South English Legendary, 402-418

- pseudo-Abdias, 336-69

ALSO SEE

- Evangelists as a group

- Apostles as a group

- St. James the Greater

- The Transfiguration

- The Last Supper

- The Crucifixion

- The apse mosaic at Monreale Cathedral

NOTES

1 Matthew 10:1-4, Mark 3:14-19, Luke 6:13-16, Acts 1:1.

2 Martinov, 361. Martinov says some images of the saint have a partridge on his hand, but I have not yet found any of that type.

3 Ryan, 53. Graesse, 59.